OUR DATA PORTAL Emergent RiskIQ Login

2022: The View from Washington DC

A White House Correspondent Looks at the Year Ahead…

Some progress in Congress is possible while the President’s slim majority exists, but legislative and regulatory inertia brought on by a sharply divided Democratic and Republican party in an election year will be the order of the day in Washington this year.

- Republicans will almost certainly regain a majority in the House, and capturing the Senate is also possible during the November mid-term elections.

- The President is likely to push through more agency level changes across the government, especially relating to environmental, social and economic priorities; but court challenges will slow implementation and leave companies in limbo.

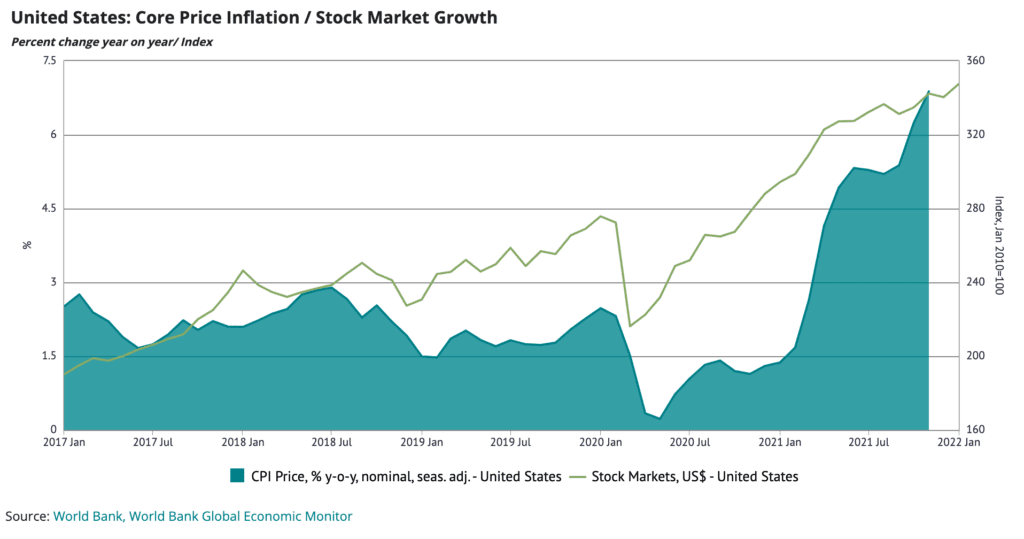

- Economic recovery will persist, but inflation and labor challenges will continue to squeeze corporate budgets and global supply chains.

When it comes to elections, it’s important to pay attention to how the data is actually distributed. For example: In the election of 2020, Joe Biden won 7,052,770 more votes than Donald Trump. Yet if only 42,918 of those votes gone the other way, Trump would now be wrapping up the first year of his second term in the White House.

Both numbers, and the way that Americans interpret them, help explain the frustration, often-misguided expectations, anger, and yes, violence, we have seen in 2021. As another difficult year comes to an end, there’s little reason to expect these emotions to dissipate in 2022. For the administration and its efforts to govern, push legislation through a bitterly divided Congress and project American unity, strength and resolve to both friends and enemies abroad, the implications are enormous.

The president’s first year in office has been somewhat typical in that it has been both successfully pro-active with the passage of a sweeping infrastructure bill, for example. But it’s also been reactive: responding to cyberattacks, weather disasters, and, of course, COVID-19.

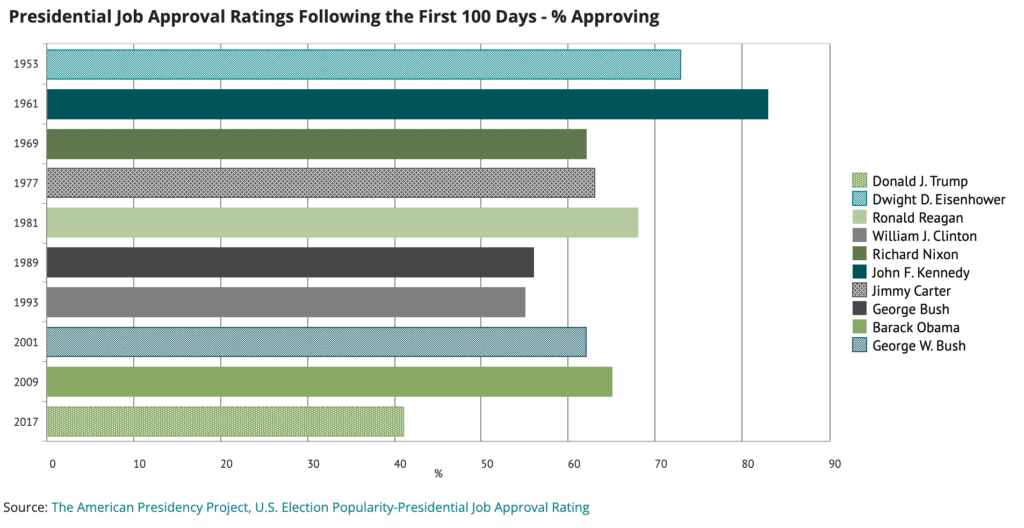

Like many—but hardly all—presidents of the modern era, Mr. Biden’s job approval began declining after he took office. What stands out among his decline: The speed of that decline. In January, two aggregate polls—FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics— put the president’s net approval at +17 percentage points and +19.5 percentage points, respectively. By mid-December, they had fallen to -7.8 and -7.5.

Swings of this magnitude in such a short period of time are reminiscent of Gerald Ford in the fall of 1974 following the Nixon pardon and a recession, Jimmy Carter in 1980 during the Iranian hostage crisis and another recession, and George H.W. Bush in 1991-92 during yet another recession. There are others, but these three presidents are mentioned because their re-election bids (in Ford’s case, merely an election bid), were dashed by the voters.

Peeling away more layers of this onion, it’s hardly noteworthy that opposition to the president from Republicans has been steady, united and fierce. What is noteworthy, however, is that support for Mr. Biden from independents—a group he won by 13 points in 2020—has collapsed. His party seems all but likely to lose its razor-thin majority in the House of Representatives; the Senate math is also discouraging for Dems. This, plus other data, and an objective look at the long sweep of history, suggests that 2022 could be the last, narrow window that Mr. Biden has to move his agenda forward.

Of course, it’s only fair to note that the dynamic that has dragged the president down in 2021 could ease or be reversed. Now that his $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill has passed, he has begun to travel the country to tout its benefits. An even bigger social spending bill could follow. The pandemic-induced supply chain problems could ebb, and with it, inflation. The number of cases from COVID-19 itself, and the subsequent Delta and now Omicron variants, could decline. Conditions are never static. Nor, the president can hope, are opinion polls.

Yet this is where we are now.

Let us now look at two things: First, the likelihood of a Republican takeover of both chambers of Congress in 2022, and the very narrow window before then that Mr. Biden has to advance his agenda.

2022 Midterm Forecast

The House: a red wave is building

Midterm elections are always about the incumbent president—and are rarely the friend of that incumbent. Since 1946, when Harry Truman’s Democrats lost 55 seats, though 2018 when Donald Trump’s Republicans lost 41, there have been 19 midterm elections. The president’s party lost ground in 17 of them — 89% of the time. The average number of seats lost by the sitting party in these 17 midterms is 29. The median is also 29, meaning that the party in power lost more than 29 seats half the time. Again: midterm elections are no friend of an incumbent president. This is particularly so when when the president’s job approval numbers are poor, which is currently the case for President Biden.

One predictor as to how Mr. Biden and the Democrats will fare in November 2022 is to examine what happened in prior midterms when the sitting president had approval ratings similar to where Mr. Biden stands now. In mid-December, two aggregate polls, FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics, each put the president’s approval at 42.9%.

For President Biden and his Democrats, Republicans don’t need an electoral tsunami to flip the House. They only need to pick up a modest five seats—far below the average and based on present conditions and the above history, a Republican takeover of the House a year from now seems an almost certainty. Now let’s look at the Senate.

The Senate: tilt to GOP likely

The Senate is evenly divided between Republicans (50 seats) and Democrats (48 plus 2 Independents who caucus with that party).

- Of the 34 seats that are up for election, 20 are Republican-controlled and 14 are Democrat-controlled. Neither of the two independent seats are up for election.

- Of the 20 Republican seats that are up for election, the Cook Political Report, an independent, non-partisan Washington newsletter, rates 15 as safe, 2 lean Republican and 3 are considered tossups.

- Of the 14 Democratic seats that are up for election, the Cook Political Report rates 10 as safe, 1 leans Democratic and 3 are considered tossups.

The Washington Outlook – the Bottom Line

As the maneuvering for the midterms consumes Washington, its raison d’être—governing on behalf of the American people—may be deemphasized. Republicans, eyeing controlling majorities in both chambers of Congress, come 2023, will see little incentive to cooperate on Democratic priorities. Regulatory and business priorities will generally lag – with Democrats likely to attempt to push through several more key pieces of legislation – but implementation will be hampered by legal challenges and political grandstanding. While bureaucratic regulatory changes aimed at addressing environmental, social and public health policy are likely to continue apace, they will also continue to be challenged in court by Republican state governments and policymakers.

One area where some progress is possible is on section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, given on-going concern about technology platforms and their control of the online information space. The legislation, which shields communications companies from prosecution over illegal activities carried out using their products, is the target of both sides of the aisle. Even this, however, will continue to be controversial and divisions along partisan lines in terms of how section 230 should be reworked will likely hamper major progress.

The Economic Outlook

After 2020’s GDP decline of 3.5%—the first decline since 2009 and the worst since 1946—the U.S. economy is on track to rebound sharply in 2021. A November analysis by the Conference Board shows GDP jumping 5.7% this year, before easing to a still respectable 3.8% in 2022 and 3.0% in 2023. The forecasts were issued before the emergence of the Omicron variant became known.

A presentation by the Board warns of numerous short-term economic risks could impact 2022 growth:

- Faster-than-expected inflation

- Financial stability

- Geopolitical risks

- Labor market disruption

- Lingering travel bans

- China economic downturn

- German auto crisis

- Another COVID-19 variant

The presentation can be seen as highly prescient, given that December 2021 saw the highest jump in inflation year on year in 40 years, just as a new COVID-19 variant took hold and new travel restrictions emerged. The United States also continues to face significant labor market disruption, as reflected in the Labor Department’s latest (September 2021) Job Openings and Labor Turnover summary, which showed 10.4 million openings and elevated numbers of Americans leaving their jobs.

As for long-term economic risks. There is plenty to choose from:

- Labor shortages

- Deglobalization

- Aging population (China and elsewhere)

- Quality of the labor force

- Climate change

- Transition costs from fossil fuel-based to green economy

- Another pandemic

- Gluts in production (deflation)

Deglobalization here means what could be a long-term move away from supply chains that have proven to be less than reliable during the pandemic, towards shorter, presumably less vulnerable supply chains that can be better controlled in the future.

Political paralysis in Washington and a variety of potentially disruptive economic forces are an unhealthy and dangerous combination. The eruption of a crisis needing urgent, bipartisan attention would be more difficult to deal with this coming year, given that some lawmakers will use crisis to grandstand and score political points, rather than actually focusing on the problem at hand. This can be regarded as a cynical observation, but one that, based on current conditions in the nation’s capital and its halls of power, is a realistic one.

Foreign Policy

On the foreign policy front, President Biden spent his first year in office attempting to re-orient America’s focus towards China. The president rightly sees the People’s Republic as a peer rival, politically, economically and militarily, and has worked to bolster economic and security with key allies like Japan, South Korea and Australia. A security pact announced in September between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States (“AUKUS”) has been praised as forward-thinking and essential to blunting Chinese influence in the Western Pacific. AUKUS will boost cooperation in cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technology and more. Not surprisingly, China condemned AUKUS immediately. The White House has also infuriated China by criticizing its “ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang.”

Whether coincidental or not, as political tensions between the United States and China have grown in recent years, so have business risks. The new year will almost certainly see a continuation of what the last few years have wrought: tariffs, export controls, and investment restrictions in technology and other sensitive areas, all of which are fueling business uncertainty and driving up costs. Costs are also rising as national security concerns drive the relocation of supply chains. Major issues like forced technology transfer, and China’s massive theft of intellectual property remain ongoing and costly matters. These issues go far beyond the strained Washington-Beijing dynamic. Leaders in the European Union, even while eying its massive market, regularly refer to China as a “systemic rival,” and are expanding assorted regulatory measures that raise both political and business risk.

There are other sources of tensions too; notably Taiwan. The People’s Republic has never governed Taiwan, yet claims sovereignty over it in accordance with its “one China” principle; Chinese President Xi Jinping has said that both must be “reunified.” The United States does not have diplomatic ties with Taiwan, yet the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act says that Washington should help Taiwan defend itself if needed.

That background aside, the broader and complicating dilemma for Biden is that while the American stance towards Beijing has been stiffened, the United States needs China’s cooperation on numerous vital matters, most notably climate change, North Korea and Iran. The United States also wants greater cooperation on thorny issues such as cyber hacking and intellectual property theft.

The president has been correct to make this bilateral relationship—certainly the world’s most important, and the most complex—his top foreign policy concern. Yet adversaries elsewhere—notably Russia, and the above-mentioned Iran and North Korea—have proven to be time-consuming distractions. To say that Mr. Biden has his work cut out for him on the global stage in 2022 is quite the understatement.

Sign up for our Newsletter

ERI has offices in the United States, Singapore, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Want to know more?