OUR DATA PORTAL Emergent RiskIQ Login

Corporations and Climate

The Sputtering Environmental Recovery

Companies and governments will increase efforts to address environmental problems this year, but deeply complex challenges and major electoral contests in 2022 will limit success.

- Efforts to address major environmental challenges will be undermined by political divisions, lack of enforcement capability and the need for radical shifts in business models to meet climate targets.

- Public and private sector institutions face deeply complex challenges to meeting expectations, including the need to avoid a too-rapid shift from traditional energy sources and a growing tide of environmental online disinformation.

- Governments responsible for reigning in pandemic-accelerated environmental degradation from illegal logging, mining and agriculture will struggle with a lack of enforcement capability, while distracted by the need to focus on economic recovery.

Rising Pressure to Act – Now

Pressure on those with the most ability to address environmental problems will increase in 2022 on the heels of the fall 2021 UN climate conference, and ahead of the US mid-term elections.

Importantly, this pressure will come from a wide variety of actors – far beyond traditional groups like Green Peace – and may take new and novel forms as more people become concerned – or directly impacted by climate change. While governments will play a leading role in these efforts, without serious reforms from companies and major changes in consumer behavior, actual progress is likely to fall flat.

According to an annual survey by Yale University, Climate Change in the American Mind, more Americans than ever agree that climate change is happening. By a magnitude of 6 to 1. Globally, 72% are concerned or very concerned about the impacts of climate change and 80% say they are willing to make changes to how they live and work to combat climate change, according to Pew Research. With more than an estimated $145 billion in natural disaster driven losses in the United States alone in 2021; those changes are coming. And while they will affect average citizens globally, the challenge in the coming years will be whether governments and business can be agile and resilient enough to drive these changes – an absolute imperative to successful climate strategy and its implementation.

The Cost of COVID

Despite mounting concerns and pressures and some notable bright spots on the environment and health outcomes, COVID-19 has likely set back progress on climate change more than it helped over the last two years. While air pollution rates initially fell in China, India and the US, they resumed once economic activity resumed. In November 2021, New Delhi, India saw its worst November since 2014 for air pollution, forcing the government to close schools and people to stay indoors. At the same time, global usage of disposable personal protective gear (PPE) has led to a massive amounts of new plastic pollution that has clogged water ways and created enormous amounts of environmental waste from disposable masks, gloves, and other PPE. Stay-at-home culture has also led to drastically increased use of delivery services, takeout food containers, shipping boxes, plastic bags and other disposable items thought to be more sanitary than reusable items. Moreover, environmental destruction increased in Ecuador, Brazil and Colombia where farmers and local settlers are clear cutting more of the rainforest for farming and increasing illegal logging and mining against a backdrop of decreased enforcement capacity, increased demand and increased economic hardship.

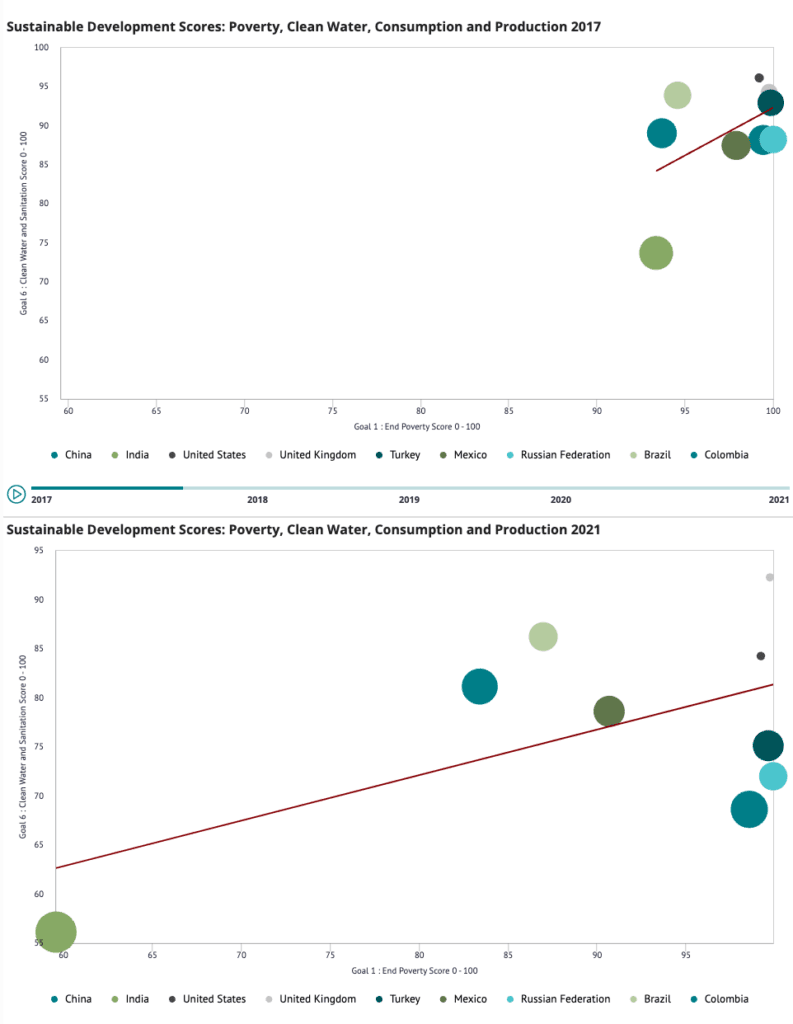

Note: The pandemic led to a setback on the UN Sustainable Development goals for most countries, with poverty and responsible consumption scores falling. Clean water and sanitation scores also fell in China and India as industrial production increased. The scores highlight a common problem for governments in achieving environmental goals as they balance the need to increase economic progress and reduce poverty simultaneously.

In the coming years, hundreds of thousands of initiatives from the United Nations, nation states, non-state actors, and the public will need to come to fruition to make a sizable dent in climate and environmental challenges. However, these changes are unlikely to emerge smoothly given the deep complexity and myriad interests with a stake in the process and outcome. Here is a look at two primary actors – companies and governments – and what their roles in contributing to environmental problems and solutions are likely to look like in 2022.

Companies

As concern over climate change grows, multinational organizations will need to increase self-policing and changes to their business models, even when it leads to reduced profit margins.

Like many other issues, but especially on the issue of climate change, multinational organizations are not passive actors – nor can they afford to be. In the coming year, companies are likely to take more active roles in addressing climate related impacts from their products – even though it may have a negative overall impact on profit. This will come in the form of more active accounting for climate impacts from their products and production processes via government mandated disclosures in countries like the US and UK and in Europe – but also more comprehensive measures of success that include minimizing environmental impact via innovative technologies and decreased energy consumption. Companies seen as directly responsible for environmental damage will continue to be a focus of environmental activists, investors and consumers seeking change including fossil fuels producers, consumer products manufacturers, food and beverage, delivery and logistics companies. However, these sectors will not be alone in being a focal point for demands for change. Financial institutions, particularly those with large corporate investment portfolios will be an ever present – and even larger target. The focus on financial underwriters as an agent of change is not new; however, as climate change has become more publicly accepted as a problem, more activists and investors have sought to cut off funding to frontline companies like fossil fuels, as a means of forcing deeper institutional change. A new report from the Sierra Club and the Center for American Progress claimed the annual carbon footprint of the eight largest US institutional investors, if they were a country, would be equivalent to the emissions of the fifth most polluting country in the world. Reports like this combined with higher visibility campaigns that target these organizations for their role in climate change – especially those waged in the direct aftermath of major natural disasters – will intensify pressure on these institutions to reconsider their investment portfolios, tipping the balance of investments towards renewables and companies enacting real solutions to environmental and social issues.

Because of this – but also due to internal pressure from employees and sometimes also driven by changing executive views on the environment – companies will be increasingly measured on real efforts at reform, regardless of the price tag. High profile shifts towards renewables will bring some accolades to companies attempting to make the shift like UK energy giant BP – but continued drilling and production of fossil fuels will put many of these same companies in a difficult bind with activists and investors who may demand more but may not have a full understanding of the consequences of winding down fossil fuel production too quickly, before global shifts to renewables can be enacted. Moreover, companies that trade in information, be they social media or traditional media, may face deeper criticism and pressure over environmental disinformation, an issue likely to grow in scope in the coming year as the US, European, and other global governments move to make deeper – and likely expensive and unpopular – regulatory efforts to address climate impacts in line with commitments made at the UN Climate Conference in Scotland in 2021 (COP26). This could include stronger calls to reign in disinformation from other governments, businesses or third-party actors who have a financial stake in limiting or thwarting regulatory reforms.

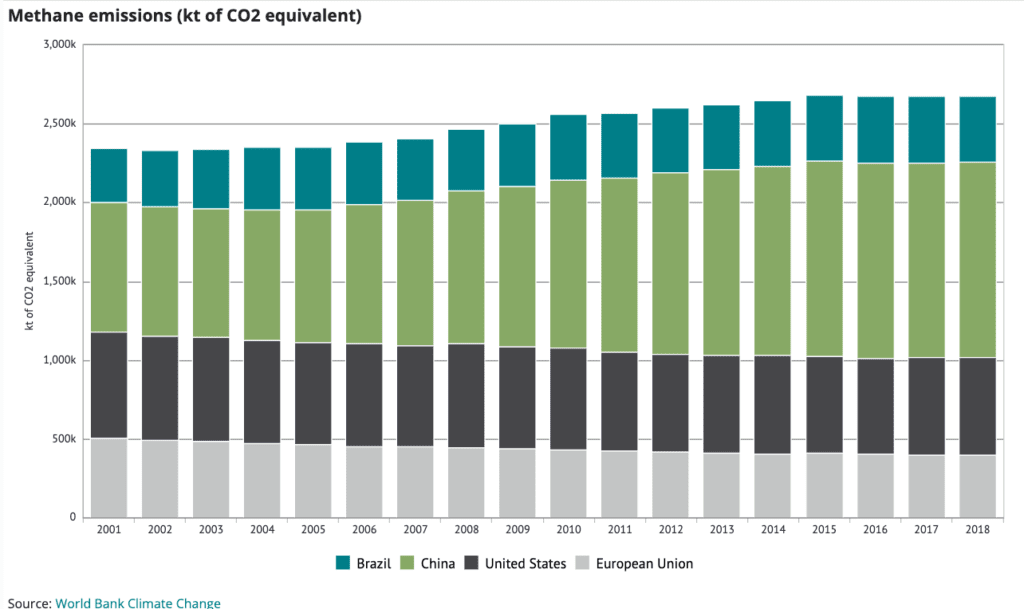

Deep and enduring change that will truly slow global warming will require companies in some industries to alter business models nearly completely. From social media companies that may need to consider how to do business without algorithms that encourage the spread of disinformation, to companies that utilize plastics for the majority of their products, broad change will be required to address some of the deepest environmental problems facing the world today. Agriculture companies and cattle ranchers may need to completely rethink their business as it pertains to meat to achieve global climate targets. According to Jais Valuer, CEO of Denmark and Europe’s largest meat producer Danish Crown, beef could become a luxury commodity in the coming 10 years, with more consumers opting for lower carbon footprint meats like pork and chicken. The company is one of many European companies to join the UN Climate Compact with a goal of contributing to reduction carbon output in line with the UN’s stated climate goals. In the United States and Brazil, the world’s top two beef producers at 20% and 17% of total global beef production respectively, reduction of cattle farming may be a harder sell. Beef accounts for 31 times the amount of emissions of chicken or pork production, but agriculture companies that supply beef to some of the world largest sellers of beef, like McDonalds, by and large still do not account for their CO2 and methane emissions. According to factory protein production tracker, the Fairr Collier index, only 18% of global agriculture companies track methane emissions – and of those – 25% increased methane output this past year. Overall, global meat production releases the methane equivalent of 3.1 gigatons of CO2 into the atmosphere each year. Underscoring the importance of industrial reform in lowering overall global warming, the industry produces as much CO2 equivalent methane as the third largest polluting country in the world, falling behind the US but ahead of India.

Note: Methane emissions are declining in the US, Brazil and EU – but increasing in China. Still, the declines are unlikely to be sufficient to meet UN Climate goals without drastic action, despite pledges from all of these countries during COP 26 this year.

Uneven development, governance and enforcement will put more heavily regulated companies at a relative disadvantage to companies in under-regulated countries, or those lacking political will or enforcement capability. China and India will likely introduce heavier regulatory changes to reign in their own carbon footprint and climate impacts – including regulating periodic shutdowns of manufacturing and other high pollution industries. However, while highly disruptive, these tactics will probably have less financial impact than reforms that require retrofitting of factories, rapid shifts to renewables, and enforcing a phasing out of automobiles utilizing fossil fuels. In China, state mandated reforms may happen faster than in India, but neither country is likely to fully embrace such changes as rapidly as required – particularly if it will harm overall economic recovery from the pandemic.

Governments

Government mandated change will be halting and unlikely to meet expectations this year, amid struggles posed by continued pandemic fallout, major election cycles and lack of enforcement capacity for environmental regulations.

Government mandated changes are crucial for comprehensive change but are likely to be watered down and in some cases thwarted altogether by deepening global political divisions as well as the need for relatively rapid economic recovery from the pandemic. In the US, meeting commitments made by US President Joe Biden at the US climate conference in 2021 is heavily dependent on the passage of the Build Back Better legislation currently sitting in Congress. Failure to pass the bill, according to recent analysis from Princeton’s REPEAT project, would lead to the country falling 1.3 billion tons of CO2 short of its 2030 climate commitments; around a 30% difference overall. Recent changes in support for the bill in the US Senate, ahead of a midterm election year that will almost certainly shift the balance of power in the House and Senate to Republican control, greatly diminish the likelihood of the bill’s passage, leaving the White House to make most changes via executive order. This piecemeal approach will not allow the comprehensive changes and financial incentives envisioned by the bill to bring these changes to fruition. Environment-related changes are likely to be less controversial in European and other democratic parliaments – but they too will continue to create backlash – particularly in instances where changes bring additional expense or hardship to lower economic classes. In 2019, attempted changes in law in line with France’s commitment to the Paris Climate Accords under French President Emil Macron led to the beginning of France’s highly disruptive and – at times violent – Yellow Vest movement. Similar, but smaller changes in chemicals allowed for farming led to repeated farmers protests in European capitals.

Governments will also be confronted with a changing manufacturing environment, with more companies and governments looking to nearshore critical supply chains that include pollution heavy industries like mining and processing rare earths – ironically – those minerals needed to create batteries, wind turbines and other renewables that are expected to lower overall carbon footprints. This too will challenge overall ability to lessen carbon footprints for government and industry. Increased demand for wind turbines, for example, is (among other factors) accelerating deforestation in Ecuador and Brazil due to sharply increasing demand for balsa wood used in creation of turbine blades. Other types of manufacturing expected to become more prominent in Western nations include water intensive microchip processing facilities, pharmaceutical and health device manufacturing due to concerns over their availability for technology innovation and infrastructure development.

Expanded organized crime impacting the environment will necessitate comprehensive policing and enforcement methods which, in developing countries, will prove a tertiary priority behind rebuilding pandemic-ravaged economies.

Public institutions will need to take broader and more comprehensive action to reduce organized criminal activity that contributes to climate change and environmental degradation. In developed countries, more initiatives to police organized crime targeting the environment is likely. In the US, FinCEN, the intelligence arm of the US Treasury, has asked banks to include monitoring for cash flows from environmental crime including illegal mining, logging, wildlife trade and hazardous substances and waste trafficking in their anti-money laundering compliance portfolio. The advisory, issued in December, is the first ever from the FinCEN, which is normally more closely focused on tracing money tied to narcotics, human and weapons trafficking and terror activity.

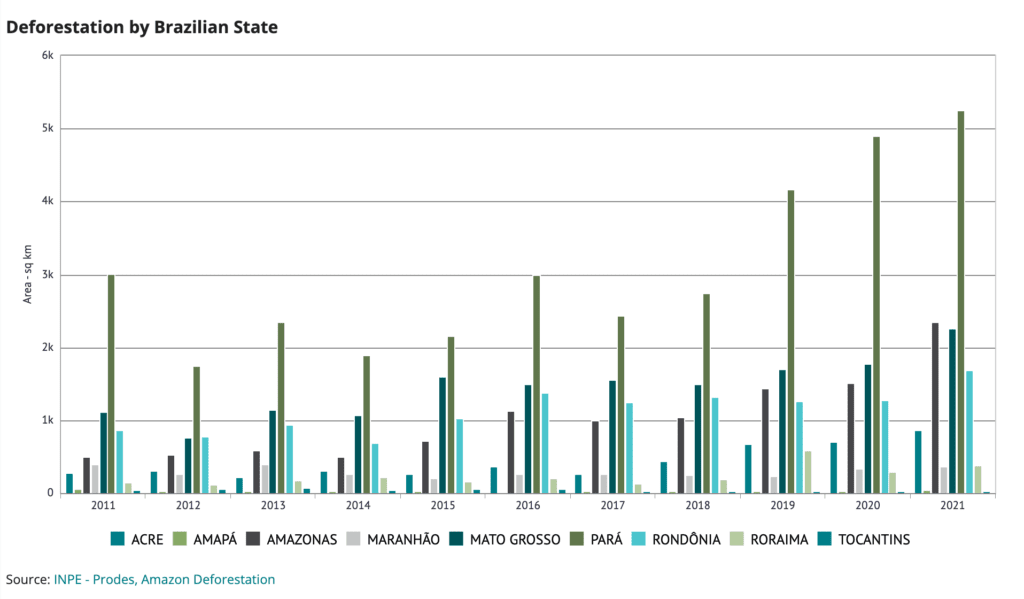

In Asia, Latin America and Africa, some of the most dangerous and damaging environmental crimes take place in states with limited to no policing capacity. Deforestation driven by land clearing for logging, illegal mining and agriculture expanded in Brazil during the last four years under President Jair Bolsonaro, to the point that the Amazon rainforest has become a net producer of CO2, rather than absorbing it. In Colombia, a lesser recognized but similar phenomenon is also affecting the Amazon and other forested areas. Here, the break-up of the FARC and the peace accords that ended a decades long civil war had the unintended consequence of opening the region’s rainforest to a wide array of destructive activities as FARC guerilla groups demobilized and gave up control of these areas. Among those were legal activity like agriculture and cattle farming, but also illegal activities including illegal logging and mining, continued and expanded cultivation and processing of crops for illegal drugs, and expansion of farming into prohibited parts of the rainforest. In the wake of the pandemic and ahead of a likely further regional wave driven by the Omicron variant, governments responsible for these highly fragile eco-systems will struggle to find the resources and, at times, the political will to address these problems in any real manner in the coming year.

Note: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon increased dramatically during the pandemic and under the leadership of President Jair Bolsonaro.

Major environmental problems, like water scarcity, will increase the likelihood of geopolitical conflict, while requiring countries, companies and communities to find a balanced and agreed upon approach to sharing resources.

Struggles to address water resources, from allocation that balances municipal with industrial needs, to addressing conflicts over shared cross-border water resources are also increasing in volume and complexity. An under-recognized, but fast-growing problem in the coming decade will be China’s quickly diminishing water resources and its impact on economic development and global security. Despite its massive geographical size, China possesses only 7% of the world’s water resources but 20% of its population. Although at one time relatively self-sufficient in agriculture and resources, as the country’s population and consumption have grown, it has moved to importing nearly three-quarters of its oil and is the largest importer of agricultural goods overall. A combination of industrial development and unchecked pollution have made as much as 80-90% of its fresh water sources unfit for human consumption, and as much as a quarter of its groundwater so contaminated that it cannot even be used for industrial purposes. While the country actively works to solve the problem, energy crunches and droughts, like the one currently facing manufacturing hubs Guangzhou and Shenzhen, will become far more common, affecting manufacturing output and supply chains globally. While China’s authoritarian system of government will allow it more control over water rationing and public usage of water resources, the problem of shared water resources – some of which come from Tibet and others from the Mekong River – a shared resource with Southeast Asia – threaten geopolitical conflict as the country increasingly sees a need to hoard more water within its borders. Meanwhile, China will face more difficult choices about how much economic development can accelerate without further harming its dwindling water supply. Here, as in other parts of the world, this challenge will increasingly become an acute problem for multinational businesses invested in these countries to address from both a regulatory perspective, as well as a position of corporate social responsibility and maintaining a license to operate in the communities where they work.

Sign up for our Newsletter

ERI has offices in the United States, Singapore, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Want to know more?