OUR DATA PORTAL Emergent RiskIQ Login

The Future of Data

Data will drive our reality in the coming decades, but it will remain highly susceptible to manipulation, government control and misuse – even as it becomes more ubiquitous.

- Rapid evolution of the online environment to “the metaverse” will take the use of data to shape our reality to new levels, bringing with it new legal, regulatory and privacy concerns.

- Lack of data literacy will lead to more real-world harm as bad actors use incomplete, poorly collected or falsified data and disinformation to create divergent realities.

- Shareholder expectations and regulatory requirements will press organizations to use more wholistic data in the boardroom and better apply it to business outcomes, increasing the need for data literacy, particularly among those collecting such data.

- A tug of war between governments and business for access to and transparency of data and its usage will play out in very different ways in democratized countries versus autocratic ones.

Data as the Bedrock of Our Reality

As data forms the basis of more of our internet-connected interactions, companies’ control of this data will be increasingly contested, scrutinized and regulated.

The pandemic accelerated humanity’s deep dive into online life with work, medical appointments, and even happy hour gatherings – moving the world more firmly into a virtual space that allowed for shared connectedness while attempting to keep people healthy. In 2022, the next evolution of this trend into a largely AI and data-driven “metaverse” looms large, holding intriguing promise as well as risks. The metaverse concept has become more widely recognized since Facebook famously changed its name to “Meta” in late October 2021 and said that it would invest heavily in the coming year in building this into a reality.1 Similarly, in late November 2022, Bill Gates predicted that by 2023, most corporate meetings will happen in the metaverse.

Like many data-driven concepts, one of the biggest risks associated with the race into this high technology frontier is a lack of public understanding of the technology and data driving these developments, and how they affect everything from legal frameworks and data privacy to physical security. Along with these concerns will come another front in the wild west of unregulated online spaces where government regulation will be slow to form and reactionary in nature, rather than proactive. While substantial scrutiny will be given to privacy and how our private data is assembled and collected in this space, it will take time for governments to fully understand it and to agree on a way to regulate it. This will include data collected from wearable devices like heart-rate monitors and movement trackers as well as consumer preferences, daily habits and movements, and physical attributes that might go into the creation of a metaverse avatar. Third parties, without proper regulatory frameworks could potentially inject their own layers of information onto these avatars, making them speak, wear certain items or label them in some form or another – creating broad questions about consent, reputation, how the space might be governed and whether people will have any control at all over their data and online persona. Moreover, renewed discussion and actual tools available for the development of a true metaverse have also triggered a new race to develop the needed networks and technologies to build out this space, with Chinese firms quickly moving to secure trademarks and technology to give them, and the country, an edge in these developments. According to the South China Morning Post, as of late November and December of 2022, over 8,500 trademark applications were filed by Chinese firms seeking to stake a claim on metaverse-related technologies. The vast majority of these were filed in the aftermath of the Facebook name change and metaverse development announcement.

For business, risk is high in this new sphere and will stem, in part, from their success or failure in building trust with consumers and others upon whom they rely on for the data that powers their platforms and revenue. Concerns about the amount of personal data held by companies like Meta, Alphabet, ByteDance, Amazon and others drive futurists’ worries about the “metaverse” and augmented reality. Specifically, companies that hold any type of personal data – from consumer tastes to personal interests to financial well-being – will come under further pressure this year and in the coming decade to ensure that they use that information responsibly, likely leading to more information leaks from whistleblowers, as well as tighter regulatory controls on information privacy. With companies now taking another run at creating augmented reality through wearable technology like glasses, a salesperson in the store of the future could, via facial recognition technologies and augmented reality, look at customers through a pair of special glasses and see them surrounded by information about their favorite brands, financial well-being, credit scores and other data. Facial recognition technologies with similar capabilities already exist and have been used – with great controversy – in China for some time to identify criminals or single out individuals that are of interest to the government for political or other reasons. The acceleration of this trend will be broadly dependent on private companies – and the level of integrity put forth to ensure responsible use of consumer data and privacy – as well as the political will to regulate responsible use of such data and technology before the technology once again outpaces government bureaucracy.

The ability to move about and perform actions in the metaverse, as if it were reality – but without the perception of the same consequences – could also give rise to more legal concerns for companies who host such spaces. For example, companies and governments may find themselves wrestling with thorny questions about whether sexual harassment directed at an avatar constitutes real-world harm to the owner of that avatar. Jurisdictional questions could also arise when such actions or accusations occur between people located in different physical spaces as to how such conduct would be policed and prosecuted under existing legal frameworks.

Disinformed about Data

Gaps in public understanding of data, verifiable information and growing cognitive dissonance over politically motivated disinformation sharpen both the need for, and the dangers of a more data-driven world.

In the disinformation era, fact-driven, provable data has become more critical than ever to the functioning of business, government and society. And while its importance will only rise, the simultaneous stagnation and degradation of public understanding of information and data – from its provenance to its use – will create greater gaps in reality between groups with opposing viewpoints, increasing the probability of conflict in some places. The “infodemic” that has driven political polarization, vaccine hesitancy and denial during the pandemic is driven in part by a society that has not kept up with changes in how we convey information, how we verify it, and how easily data and information can be manipulated. While not the sole cause of the greater political extremes evident globally, data illiteracy is compounding the problem. In some countries’ education systems, data usage will become more foundational to teaching outcomes and decision-making. However, in countries like the US, ideological fights over curriculum will limit progress in teaching sound data science principles and research methodology at a foundational level. Data and technology processes in the works today that allow the tracing of information – near-instantaneously – to its original source will assist companies in better understanding the information landscape in the coming years and may chip away at the foundations of disinformation driving these fissures in society over time but will be unlikely to convince the most ideologically-focused of the population of the true source of their strongly held beliefs.

In business, decisions will become more wholly and necessarily rooted in provable data, particularly as new “data native” leaders emerge to challenge traditional decision-making. In an era of social and environmental consciousness, companies will be challenged to consider far more than financial data in business calculations. Environmental and social impact data, alongside other data that can back assertions that products and services create more good than harm, will be increasingly important in investment decisions and corporate reporting. This will necessarily require any function that supports executive decision-making to have a sound understanding of how to integrate data into research processes and analysis outcomes. Climate-related disclosures, for example, will almost certainly form part of the 2022 regulatory environment, with the SEC period for public comments on US climate disclosure rule-making drawing to a close in the summer of 2021. Comments from companies, associations and impacted groups have ranged from resistant, to urging the SEC to go further with the rules to include disclosures on indigenous rights and social justice-related initiatives. The final regulation will probably rely heavily on companies’ use of demographic, environmental and economic data to calculate these impacts – which would then be a part of annual reporting requirements to the US government. In the United Kingdom, climate-related calculations and disclosures are already slated for mandatory reporting in 2022, while in the rest of Europe, these mandates have been in place since 2019. Developing countries – particularly those that are heavily impacted by climate change, are also likely to push businesses for data-driven information about the impact of their activities within their borders. In these places, industrial pollution from developed countries is blamed for disproportionate impacts despite these countries having not benefitted from industrialization. Security and health and safety-related decision-making will necessarily require workforces to become better grounded in these same types of data to answer leadership questions and requirements. The drive for global reporting on COVID-19 related data for the last two years has only accelerated this trend and will result in more companies embedding this type of reporting across all related decision-making – increasing the need for better data on everything from security trends to the impacts of pollution on employees and surrounding communities.

Data Integrity

The integrity of data and the use of bad or misleading data in decision-making processes threatens faulty outcomes that heighten rather than reduce risk.

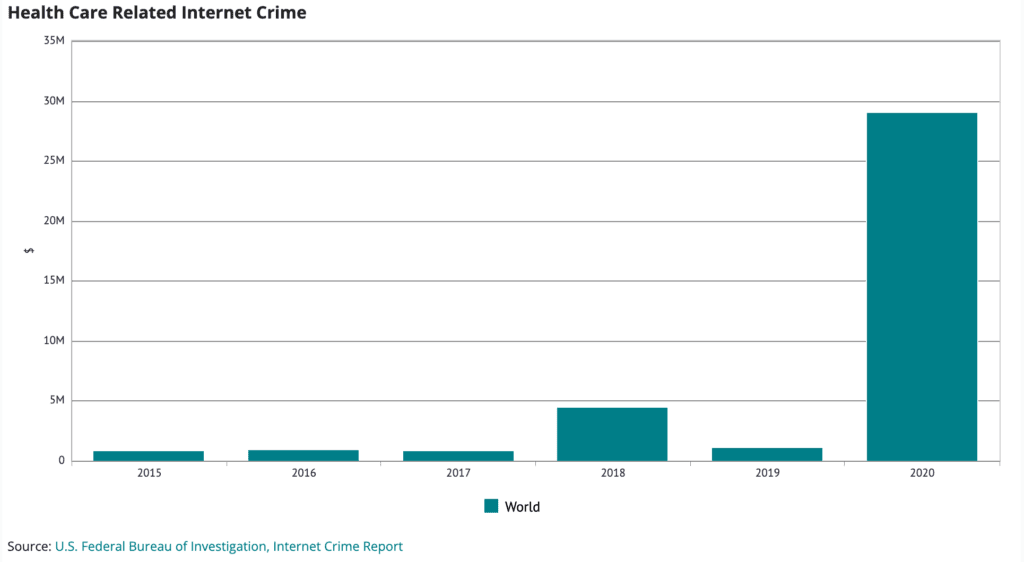

As with the entire information universe, data integrity will become an increasing concern. Data – which is fundamentally just information collected in massive volumes – is subject to the same types of manipulation as other information. The integrity of medical data – which became a popular target for hackers and economic espionage during the pandemic – can have existential consequences when adulterated or compromised. In the coming years, this will become an even weightier issue with ever more sophisticated cyber threats potentially evolving from simple ransomware attacks to more sophisticated attacks that threaten data integrity of medical devices and medical records. A simple mixing of data showing patient blood types, for example, could bring a medical system to a halt – and require months and years of fixes, while manipulation of data used in life-saving medical devices, like pacemakers, could have fatal consequences for users. Similarly, manipulation of data feeding major transportation systems, industrial control (SCADA) systems and the financial system remains an existential threat with as many new threats arising each day as solutions.

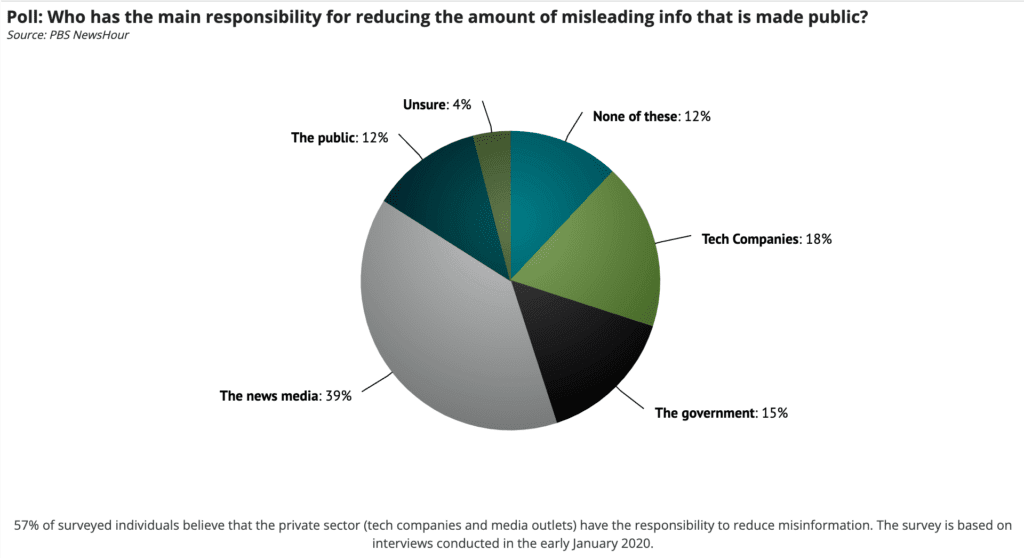

Meanwhile, the adulteration of data in the online world, from simple manipulation of charts used to mislead an audience about a particular topic, like vaccines or political issues, to more sophisticated creation of studies that do not meet scientific, peer-reviewed standards or the use of polling that is not statistically sound has an increasingly strong impact on shaping public opinion and decisions. A recent report in Scientific American noted that more non-replicable studies are cited in mainstream news publications than ones that have been peer-reviewed and replicated, underscoring a broader trend of deteriorating quality in studies and creation of poor data upon which to base broader decision making. While some of this data and information is created with no malign intent, data and studies created to intentionally back a particular worldview or ideological aim are becoming more common. Among other problems, public ignorance of basic data science and analysis has allowed such bad data to seep into decision-making processes at the highest levels of government and business in the last decade.

The Role of Companies

Organizations will need to be proactive in protecting user data and ensuring ethical use of such data to head off or at least minimize the impact of major regulatory reforms aimed at curbing the power of corporations and the data that they possess.

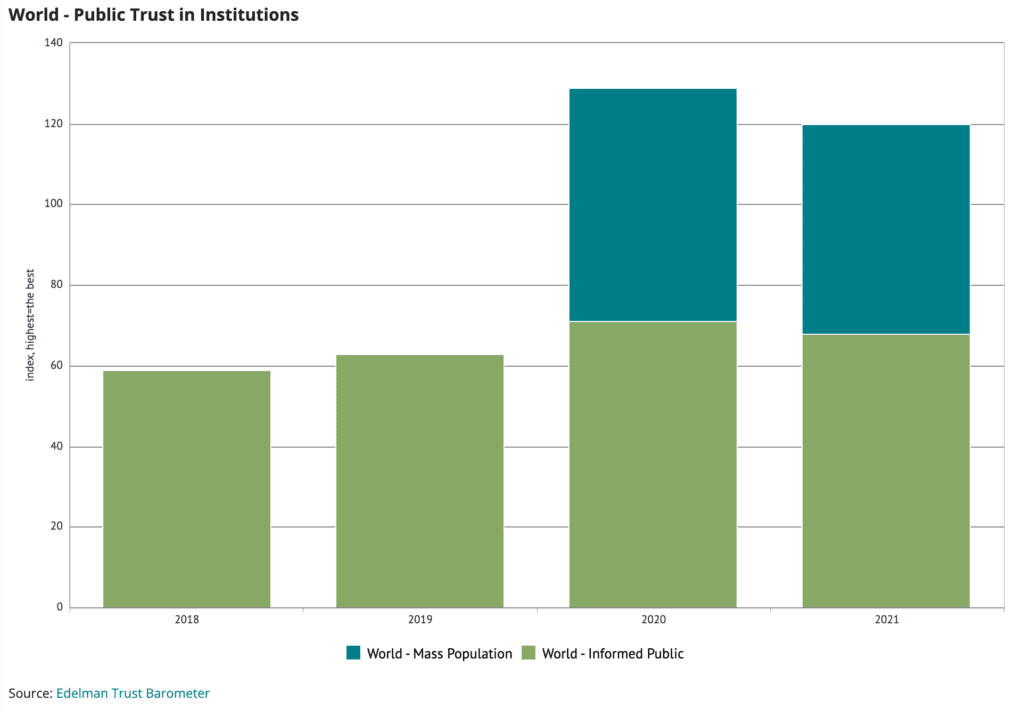

Corporations are among the largest and most powerful owners of data on the planet. Major information leaks from employees at leading brands like Google, Twitter or Facebook will drive headlines, but behind those headlines and political posturing, government efforts to better understand and control data from companies will have mixed outcomes this year.

2022 will see more governments attempting to remove – or at least heavily regulate technology and data driven power within large organizations – and to address perceived unchecked power created by control of such volumes and diversity of data. In open democratic societies, there will be attempts at transparency and governing data for the greater good. Elimination of algorithmic bias, stove-piping of political information that drives extremes on both ends of the spectrum and attempts to root out political manipulation of data and information through social media will continue. However, in the US, this will mostly be limited to congressional hearings and political grandstanding, with 2022 mid-term elections and control of the House and Senate looming large. Revision of section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, however, is possible in some form – most likely around information targeting children and young adults, while broader control of data and free speech will remain at issue between major political parties due to the way that each party benefits from a current lack of control over political speech online. More interestingly, algorithms themselves could be considered for removal from protection under Section 230. A recent policy recommendation from an expert group at the Aspen Security Institute suggested that they should be excluded from coverage under the act as they are computer and AI-generated. A move in this direction would drastically change the way social media companies run their platforms, potentially reducing the prevalence of hate speech and other extreme media that thrive due to algorithmic bias.

In more closed societies, governments will wrest more data control and power away from corporations – likely to follow China’s lead, to the detriment of citizens in those countries and the world. In some countries, this will lead more companies to exit these markets as increasingly opaque government expectations of compliance with policies that discriminate against ethnic, political or social groups and lack of control over intellectual property become more common. Publicly held companies are substantially more transparent in their use of data than undemocratic governments and can be held to account by shareholders, the media and regulators in democratic societies. However, in countries where democracy is in retreat, companies face continuing challenges in maintaining an ethical business culture. In countries like China, this trajectory has long been drawn, with national security-oriented laws pulling control over data back to the state since the mid-2010s. With the pandemic and increasingly aggressive Western postures over human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong, Beijing has greatly limited data freedom, not only of its own data but that of every organization and individual operating within its borders. As this regulatory effort progresses, companies will again be forced into the position of deciding whether to halt operations in China or to create new business practices that will necessarily create walls between their China-based operations and other nodes of their international business. Smaller countries will monitor the Chinese data experiment for signs of success, looking to emulate similar policies that shield these regimes from outside accusations of rights abuses, corruption and other anti-democratic activities. Recent moves to block access to maritime Automatic Information Systems (AIS) data within its maritime boundaries bodes poorly for transparency in the country, but also safety and security in the disputed South China Sea.

Multinational companies will have the power to change or modify some regulatory requirements this year in terms of data control, much of it predicated on whether the country in question needs the company and its investment more or vice versa. In this manner, Central Asian countries like Kazakhstan that are broadly seeking to control technology companies’ control over data through localization processes are likely to be far less successful in these requirements than China, which continues to grow its own domestic companies that can remain economically viable independent of overseas investment. At the same time, these companies will be pressed harder and more thoroughly by both international and domestic activists and stakeholders to ensure that their use of local data and creation of local products and services do not create harm. A new lawsuit currently making its way through court systems in the US and UK that seeks to hold Meta responsible for anti-Rohingya content that accusers say led to “genocidal violence” in Myanmar in 2017 could be precedent-setting for how companies are held liable for such content and control of data and algorithms in the coming years. Similar accusations in Ethiopia will ensure a stronger focus on whether data and technology can be ethically deployed in these countries without interference from political actors that force the companies into complicity in unethical and often deadly conflict.

Sign up for our Newsletter

ERI has offices in the United States, Singapore, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Want to know more?